When I was working at Toyota we had an interesting conundrum. The company culture was built on incrementalism (kaizen) but we wanted to get to net zero carbon, water, and waste. Can incrementalism get you to zero? Or should incrementalism be discarded in favor of radical, revolutionary thinking? Or is it both?

Well, it turns out, the answer depends on how you measure it. By our old metrics, incrementalism would never get us to zero, but with the right thinking and reimagining how we measure progress, we could harness the power of incrementalism and be true to our organizational culture.

Always Closer, Never There

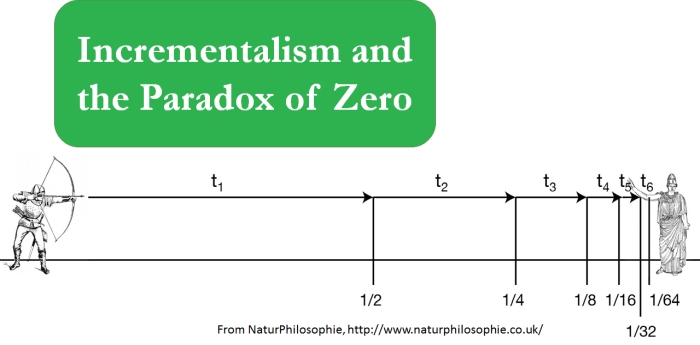

Our first challenge was the way we were setting targets. Initially we would set targets as a 1-2% per year decrease from a baseline which was reset every 5 years (e.g. by 2006 get 10% better than we were in 2001, then by 2011 get 10% better than we were in 2006, etc.). It was a past-looking way to plan – basing targets on where we’d been. And while this way of setting targets helped to address some challenges (like how to handle exceeded targets or how to cope with big changes in the market or supply chain), it meant that we would never get to zero. In the purest mathematical sense, we were heading towards an asymptote and would always get closer but make less progress each year. As we shifted our baseline each time, the absolute progress that 10% described got smaller and smaller. We were on Zeno’s Paradox of sustainability – always getting closer to, but never reaching, the hallowed zero.

To demonstrate, let’s pick an aggressive 10% improvement per year: if we made 100 tons of waste in year one, succeeding at a 10% reduction target meant that we reduced 10 tons of waste and created 90 tons of waste in year two. Our next 10% reduction target from the new 90 ton baseline meant that we reduced 9 tons of waste and now created 81 tons. Another 10% reduced 8.1 tons, then 7.3, 6.6, and 5.9 tons reduced.

In four short years we’ve reduced our waste by 25% from our starting point. To get to a 50% reduction takes 8 years (another 25% in 4 years, not bad). To get to 75% takes 14 years (another 25% in 6 years – slowing down). Past that things really slow – it’s another 9 years before we get to 90% and 22 additional years before we get to 99%. Our moving baseline means that zero is always out of reach and we expect less progress from ourselves each year.

With a narrow scope, that pacing makes sense. The early gains in any efficiency effort are easy – you first tackle the “low-hanging fruit” that are easy to implement with big gains. It’s natural to see diminishing returns as the easier stuff gets done, leaving behind increasingly difficult improvements. But at some point, incrementalism stops working on its current path and needs a new one.

Broadening our Horizons

The second challenge was that, as my friend and colleague Dave Absher put it, “you can’t efficient your way to zero.” If you take the example of energy and carbon, you can’t change light bulbs and motors to more efficient versions and expect to ever reach zero – you’ll always need some energy to drive your process. This drove us to expand the scope of consideration in a couple of ways.

The first is to shift from zero energy to zero net carbon. The focus on carbon is a decent proxy for measuring the harm that came from energy and gives us more flexibility in actions we can take and where to spend limited improvement funds. For instance, improving a facility in Kentucky (with its largely coal-based, carbon-intensive power) reaps much more of a carbon benefit than an improvement reducing the same electricity consumption in California (with a grid carbon intensity about half of Kentucky’s). And by shifting from “zero” to “zero net” it broadened our scope to total impact on the world, allowing for things like offsets, partnerships, and other efforts to improve the world.

The second change was to expand our scope from just consumption to also include generation. Specific to energy, there were three factors that would change over time:

- The amount of energy we needed (decreasing over time, but never zero)

- The carbon impact of energy from outside suppliers (likely decreasing over time but not nearly fast enough for our targets)

- Our ability to generate carbonless energy (renewable power, either onsite or offsite)

Of course, these three factors all work together to incrementally bring our net carbon to zero and potentially into negatives with surplus generation. It also opens the door to purchasing offsets, but this instrument was infrequently used at Toyota, where it was deemed preferable to spend the funds on our own improvements rather than fund someone else’s. Approaches to water and waste were similar, though sufficiently different to warrant their own discussion in future posts.

Putting It All Together

As with many things in the world of lean thinking, once we were able to see the problem clearly, coming up with a solution was the easy part. Once we understood the challenges, we were able to reimagine our targets such that incrementalism could be useful again. Setting targets based on a fixed baseline and broadening the scope of what was included allowed us to orient toward zero on a future-looking timeline, rather than our older past-looking methods. It also gave us the flexibility to make progress in different ways so that we were able to shift focus when facing diminishing returns in one method.

In 2016, Toyota announced the 2050 challenge with targets to reach net zero on carbon, water, and waste by 2050. Since we were already operating on 5-year Environmental Action Plans, we now had a clear structure for thinking about our activities: we would have seven 5-year plans to reach zero, using 2010 as a fixed baseline. We could then plan out seven milestones and begin the internal conversation to work toward consensus on how to get there. Incrementalism was restored and kaizen could resume because we had innovated the path itself.